- Visitors

- Researchers

- Students

- Community

- Information for the tourist

- Hours and fees

- How to get?

- Virtual tours

- Classic route

- Mystical route

- Specialized route

- Site museum

- Know the town

- Cultural Spaces

- Cao Museum

- Huaca Cao Viejo

- Huaca Prieta

- Huaca Cortada

- Ceremonial Well

- Walls

- Play at home

- Puzzle

- Trivia

- Memorize

- Crosswords

- Alphabet soup

- Crafts

- Pac-Man Moche

- Workshops and Inventory

- Micro-workshops

- Collections inventory

- News

- Researchers

- Landscape and resources in Moche times

News

CategoriesSelect the category you want to see:

International academic cooperation between the Wiese Foundation and Universidad Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul ...

Clothing at El Brujo: footwear ...

To receive new news.

Por: Erick Ernesto Acero Shapiama y Edson J. Palomino Rojas

By: Erick Ernesto Acero Shapiama and Edson J. Palomino Rojas

The El Brujo Archaeological Complex began its research at the beginning of 1990. After a prolonged pause, after almost 10 years, the field work is resumed through a public investment project under the Works-for-Taxes (OXI) modality. These activities are being conducted in the East Annex, and on the upper platform of the Huaca Cao Viejo, which allows us to understand a little more about the Mochica men and women who lived during the apogee of the Huaca.

The information obtained from the works carried out turns out to be relevant to understand (1) that the Mochica population knew their social and natural environment, which allowed them to take advantage of the resources they had at their disposal (food and raw materials), and (2) that the population had a process of adaptation and accumulation of knowledge, which occurred over the years and that surely was passed on from person to person, and from generation to generation (knowledge).

Thanks to recent research we can outline some scopes.

Architecture: Mochica strategic constructions

The Mochica society, which inhabited the El Brujo Archaeological Complex between the years 100 and 800 AD, undertook the task of constructing its buildings strategically, settling on elevated and irregular surfaces, formed by geological terraces of alluvial origin (Leiva et al, 2018; Gálvez, 2019).

The strategic location of buildings on geological terraces has been identified in Huaca Prieta, Huaca Cortada, Huaca Cao Viejo, the small mounds of the colonial area, and probably others that have not yet been registered; these places being recognized as safe against floods and natural disasters from washout (Bazán, 2020 - personal communication).

There are reports that mention that there were torrential rains and landslides originated by the El Niño Phenomenon –ENSOS, which generated engulfment and affected the constructions located on the valley plain, but did not destroy those that were made on the terraces, such as the Huaca Cao Viejo. This structure shows evidence that it has gone through periods of heavy rain, which have been reported and associated with its sequence of four superimposed buildings, remodeled since the Early Moche period (Franco et al, 2003; Franco, 2016). Thanks to its strategic location, it was not much affected.

The geographical environment and the economy of the Mochica epoch

The Moche Huacas of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex are located near the sea coast, bordering the sea, extensive farmlands, mangroves, cattail groves and water mirrors. During the Mochica apogee, the surroundings of the temples must have presented better climatic or natural conditions and resources.

The information regarding the ancient environment allows us to deepen our knowledge about the population of that epoch, who developed a diverse economy: they used materials provided by nature for the construction of buildings and as sources of inspiration for iconographic representations (religious beliefs). This environment also allowed the development of activities such as fishing, gathering, hunting, agriculture and fruit extraction.

This helps us to propose the following division related to economically exploitable zones for the Moche period:

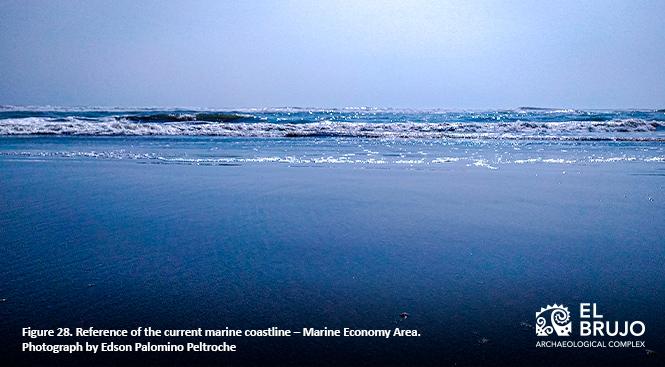

Marine Economy Area, located to the west and made up of the entire strip of the marine coastline and the current beaches of La Bocana and El Brujo, from where the inhabitants obtained certain resources for their consumption: mollusks, crustaceans, fish, birds, marine mammals and others.

The agricultural Economy Area was offered by all the part towards the valley, away from the sea. It is characterized by being an extensive agricultural land, from where consumable materials such as cereals, legumes and fruits were obtained. Also, small forests appeared here, where a varied fauna would arrive.

The Economy Area in swamps must have occurred in smaller amounts, within and around the agricultural area, made up of swampy surfaces and with an almost superficial groundwater, as well as water seepage that formed pools or ponds. From here, fibers and reeds were obtained for the elaboration of various fabrics. They also extracted some fish, such as mullet (Mugil cephalus), because it is able to withstand the changes in salinity between the sea and the wetlands (Dillehay et al, 2017), and Peruvian catfish (Trichomycterus punctulatus), which are presented in the iconography and live in stagnant waters and small cavities or water mirrors (Gálvez & Runcio, 2009).

The Moche settlers and the Huaca Cao Viejo

Research allows us to understand that the life of the Mochica of ancient Peru was very different compared to today. The characteristic natural environment showed deserted spaces, distant and diverse vegetation and a harsh climate with high temperatures. Despite these conditions, the valley was very rich due to the presence of water throughout the year.

The Moche managed to know and dominate their environment, and explore the resources that would be useful to them, both for the construction and for the development of their people. This knowledge highlights the importance of natural resources as indispensable elements employed by human groups.

The review of some works (Leiva et al, 2018; Alva, 2020), has made it possible to complement the results obtained by the OXI project. Based on this, we know a little more about the economy and extractive areas, as well as the resources obtained and used by the Mochica population who lived during the construction and operation of the Huaca Cao Viejo.

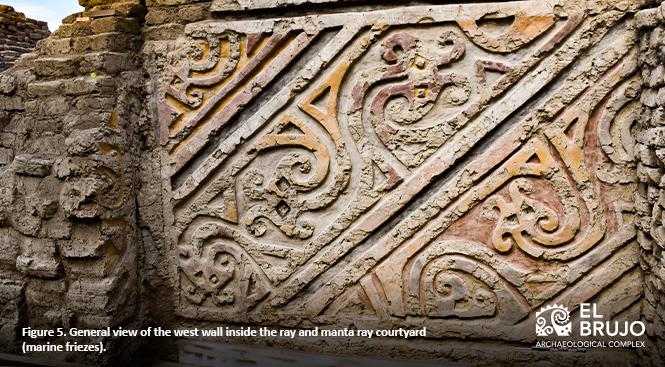

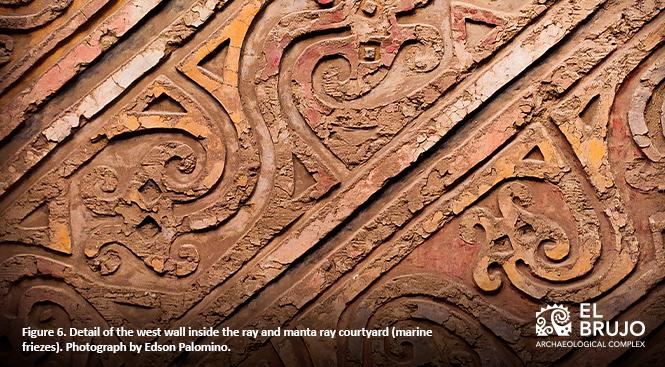

The marine resources were basically found within the construction and architectural fillings, where it was possible to recognize certain species that still inhabit today: Choro zapato (Choromytilus chorus), Choro común (Aulacomya atra), Palabritas (Donax obesulus), Black snail or turban: (Prisogaster niger or Tegula atra), among others. There were some fish (anchoveta?) that were consumed and others idealized in the iconographic representations associated with the architecture of the ceremonial rooms, such as the Peruvian catfish (Trichomycterus punctulatus) and the manta ray (Mobula birostris), whose figures were later covered during the stages of remodeling of the Huaca.

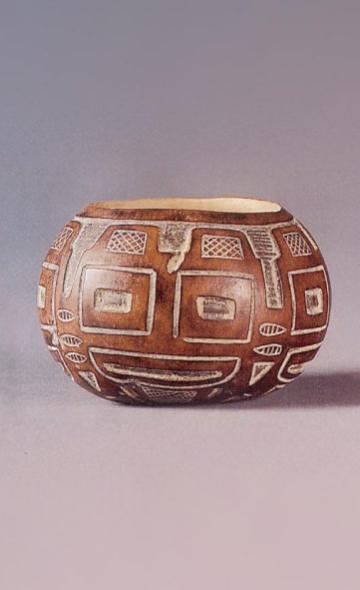

Agricultural resources and swampy areas could have been used in different ways: peanuts (Arachys hypogaea) were consumed, as there are shell remains in mortars and adobes, gourds (Lagenaria siceraria) must have been part of people's daily use, but also used as offerings, as it is found as part of the ritual burial process of some enclosures. Furthermore, part of the vegetation of the riparian forest was used in the architecture for the mooring of certain elements during construction, such as bulrush (Schoenoplectus californicus), soguilla (rush) and wild cane (Gynerium sagittatum), found as part of the upper support in niches, and the Guayaquil cane (Guadua angustifolia), as part of the support of the only window found in the excavations; all this, recorded during the last excavations in the West Enclosures.

Evidence of the proteins consumed by the Moche population in the Huaca Cao Viejo

During the work activities, the population had to invest time and effort. Therefore, they had to consume not only vegetable foodstuffs, fruits and marine products, but also meat as part of the balanced and necessary diet for the intake of the energy needed to carry out daily tasks.

Apparently, the products consumed with the highest concentration of meat and protein, came from the sea and the land. This gives us an idea of economic complementarity, since we have found fragmented bone remains of sea lions (Otaria flavescens) inside the adobes. According to Muñoz (2017), these mammals provide a large amount of meat: the adult male weighs 300 kg. (2 to 3 m long), the adult female weighs between 144 kg. (1.8 m long) and a calf weighs 10 to 15 kg (85 cm long), proving to be an energy source and sustenance for human populations on the coastline.

Moreover, there are camelid marks or footprints (possibly llama or vicuña?) and some skeletal remains, impregnated on the outside of the adobes and inside the mortars. Which suggests that they were also consumed, in addition to being employed for transportation (Prieto et al, 2014).

Our reports were compared with the studies carried out in the Huaca del Sol y la Luna, where there is ample evidence of Vicuña (Vicugna vicugna), Alpaca (Vicugna pacos), Llama (Lama glama) and Guanaco (Lama guanicoe) (Rojas, 2018), leading us to think that the Mochica people not only had to consume the meat of various animals, but that they were also able to use them in different ways. It is known that camelids are used as pack animals and that their fibers are used for weaving.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Alva Ch. J. (September 21, 2020 - accessed December 25, 2020). Mochica Agriculture: Food and Farmers. El Brujo Archaeological Complex. Recovered from https://www.elbrujo.pe/blog/la-agricultura-mochica-los-alimentos-y-los-campesinos/

Bazán, A. (December 29, 2020). Strategic location of buildings (personal communication).

Bazán A. and Chavarría, H. (November 20, 2019 - accessed December 25, 2020). The underground world of the El Brujo Archaeological Complex: The ceremonial well. Recovered from https://www.elbrujo.pe/blog/pozo-ceremonial-mundo-subterraneo/

Chavarría, H. and Alva Ch. J. (accessed December 25, 2020). A Moche temple in the El Brujo Archaeological Complex. Recovered from https://www.elbrujo.pe/explora-el-complejo/principales-monumentos/huaca-cao-viejo/

Dillehay, T. D. et al (2017). Simple technologies and diverse food strategies of the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene at Huaca Prieta, Coastal Peru. Science Advances, 1-13.

Franco, R. (2003). Models, function and chronology of the Huaca Cao Viejo, the El Brujo complex. Moche: towards the end of the millennium. Proceedings of the Second Colloquium on Moche Culture (Trujillo, August 1 to 7, 1999). Uceda & Mujica (Edit.). T. II, 125-177. Lima: Universidad Nacional de Trujillo y Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Franco, R. (2016). 25 years of archaeological research and heritage management in the El Brujo Complex, north coast of Peru. Proceedings I National Congress of Archeology. Volume I.

Gálvez Mora, C. & Runcio, A. (2009) Life (Trichomycterus SP.) and its importance in Mochica iconography. ARCHAEOBIES. Andean archaeological and palaeogeological research center. 3 (1).

Gálvez Mora, C. (2019) Architecture, landscape and time in Huaca Cao Viejo, El Brujo complex. Quingnam (5), 47-82.

Leiva González, S. et al (2018). Flora and fauna of the El Brujo archaeological complex, Ascope, La Libertad region, Peru. Arnaldoa, 25 (1), 195-226.

Muñoz, A. (2017) The exploitation of sea lions by land hunter-gatherers from Tierra del Fuego. Sea and Land Hunters. Recent Studies in Fuegian Archeology. J. Oría and A. M. Tívoli (Edit.). Cultural Publisher Tierra del Fuego and Museum of the End of the World, Ushuaia.

Prieto, G., Goepfert, N., Valladares, K., & Vilela, J. (2014). Sacrifices of children, adolescents and young camelids during the Late Intermediate in the Periphery of Chan Chan, Moche Valley, North Coast of Peru. Archeology and Society, 255-296.

Rojas Cusi, P. (2018) Exploitation of camelids during the Mochica III and Mochica IV phases in the architectural complex 35 of the Huacas del Sol y de la Luna archaeological complex. An osteometric approach. ARCHAEOBIOS Journal, 12 (1).

LEGENDS

FIGURE 1. General view from East to West of the Huaca Cao Viejo. Photograph by Edson Palomino.

FIGURE 2. Reference of the current marine coastline – Marine Economy Area. Photograph by Mary Ávila Peltroche.

FIGURE 2B. Reference of the current marine coastline – Marine Economy Area. Photograph by Edson Palomino.

FIGURE 3. Reference of the current growing area – Agricultural Economy Area. Photograph by Edson Palomino.

FIGURE 4. Reference of vegetation that grows in swampy areas – Economy Area in swamps. Photograph by Edson Palomino.

FIGURE 5. General view of the west wall inside the patio of the rays and manta rays (marine friezes). Photograph by Edson Palomino.

FIGURE 6. Detail of the west wall inside the courtyard of the rays and manta rays (marine friezes). Photograph by Edson Palomino.

FIGURE 7. Detail of the gourds found within the closure fillings, recovered during the OXI 2020 excavation process. Photograph by Mary Ávila Peltroche.

FIGURE 8. Detail of the niches with closed wild cane lintels, found to the west of the courtyard of the rays and manta rays (marine friezes). Photograph by Erick Acero.

FIGURE 9. Excavated detail of the head of the wall with two niches. A group of wild cane is shown tied with vegetal fiber that formed lintels. Found west of the courtyard of the rays and manta rays (marine friezes). Photograph by Erick Acero.

FIGURE 10. Detail of the skeletal remains of a camelid found inside the mortar used in the construction of the interlocking adobe blocks during the excavations of the OXI 2020 project. Photograph by Mary Ávila Peltroche.

Researchers , outstanding news